I once lived in Berlin. I was 19, and alchemically thin. I earned essentially no money, getting fired from dead end jobs and doing nude photoshoots for local 'artists, subsisting on partying and 10 cent Brötchen. I shared a single bed top and tail, read Russian literature, and played Shogun. It was amazing.

But, after a while, I noticed something. I would often meet people twice my age, still thin, still partying. This made me question things. No matter how amazing it is, you can't live in Berlin forever. That's why I had a child.

Read MoreStartup advice doesn't work

The strangest thing about startup advice is that either it doesn't seem to work, or people don't read it. If it worked and people read it, good startups would be more and more common. But they're not. I haven't run the numbers, but no investor I've ever met has told me that startups succeed more often now than before.

Most things aren't like startups, and it'd be terrible if they were. If the lessons from civil engineering didn't hold from one building to the next, we wouldn't have anywhere to live.

And yet, people do seem to read startup advice or, at least, want it enough that there are endless books and companies and universities dedicated to giving it. I've even given a lot of it myself over the years, whether people wanted me to or not. I think the conclusion, therefore, has to be that startup advice just doesn't work.

Read MoreSome people have a knack for languages. They say annoying things like "Portuguese is just Spanish with an accent", or "we speak French to the kids". Fuck those people.

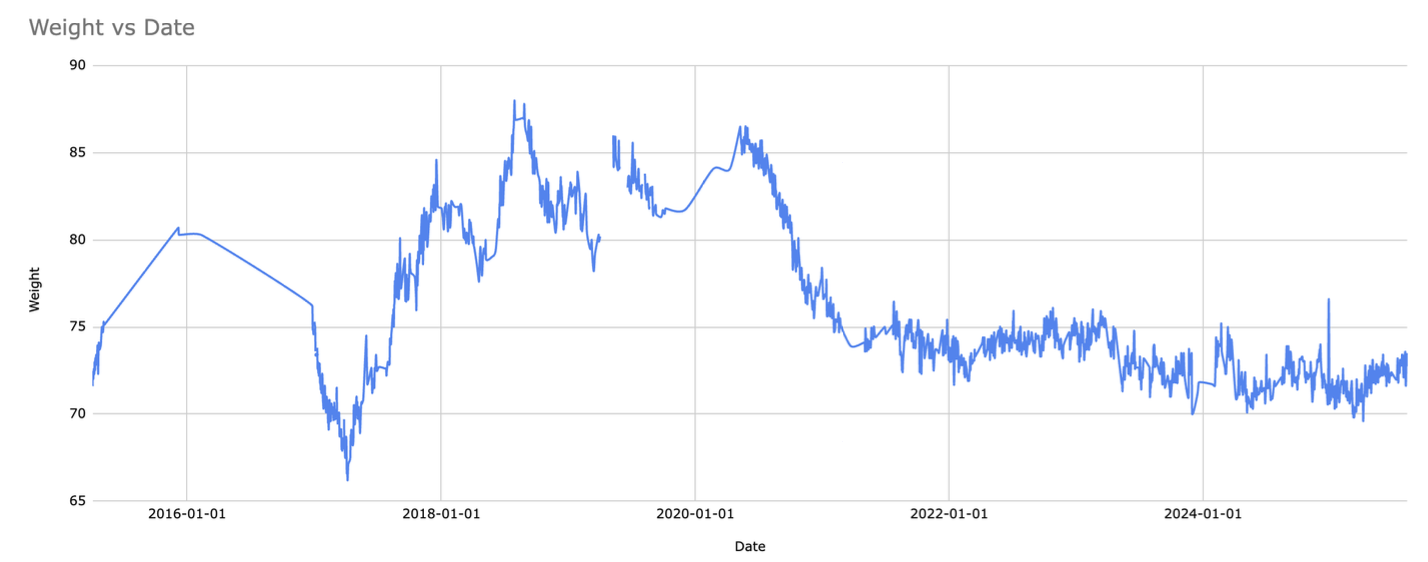

Read MoreAn 80/20 Blueprint guide to being happy, healthy, and hench, from a middle aged dad.

Read MoreYour knight for my pawn, and you have to take it. Things are about to get worse, sunshine. This is my game now. You have been out-calculated. I don't want the piece, I want your soul. My attack hurts like a school disco and I'm going to sac sac mate until... wait. What? 10 seconds left. But, I'm winning, right? I must be like +5 right now. Just play any move. But how do you have 10 minutes on your clock? Anyway, just play any move. That one will do, fine. For. Fuck's. Sake. Any move but that move! How could I instantly find the one move that loses? Literally, I could have played anything el...

Read More